Introduction

The Battle of Ap Bac used to be a little known, or understood, battle of the Vietnam War. Neil Sheehan brought it to prominence in his 1989 epic, A Bright Shining Lie. Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s featured it in Episode 2 of their documentary The Vietnam War, and now it is the focus of the latest Vietnam War novel, True North.

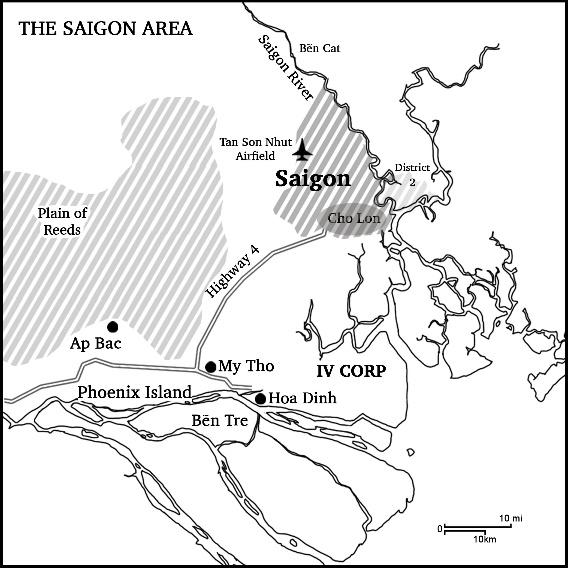

The battle itself took place in the rice paddies of the Mekong Delta on 2 January 1963 (see map below) and was a portent for the eventual failure in South Vietnam. At the time the Battle of Ap Bac was touted by Saigon HQ and the senior journalists back in DC as a major victory.

Only Neil Sheehan saw the significance of the battle. One of a handful of American junior reporters in the field at the time, Sheehan was a junior reporter for the New York Times and choppered down to Ap Bac after hearing the VC had shot down five US piloted helicopters – an unheard of occurrence in the ‘hit and run’ war at the time. Standing in the darkness away from the embarrassed ARVN officers, Sheehan interviewed the US Advisory Team 4 commander Lt. Colonel John Paul Vann, who criticised the mishandling of the engagement by the Saigon commanders. Quoting a ‘senior US Army source’, Sheehan’s article asked ‘Are We Winning in Vietnam?’ and was criticised by US Army Generals, questioned by his Editor and drew the ire of the White House.

Why was Sheehan’s article so incendiary? Because at the time the senior reporters, especially those back in DC, wanted to support President Kennedy. American ‘exceptionalism’ was in full effect and pushing all the doubters out of decisionmaking positions. Besides, how could they be getting it wrong in Vietnam if the White House was staffed by the ‘Best and the Brightest’ of their generation? And who was this junior reporter in the field who had raised the spectre of the anti-Communist crusade not working?

Fast Forward

Fifteen years later Neil Sheehan propelled this forgotten battle into the American consciousness in 1988 with his book, A Bright Shining Lie. Sheehan was one of the first authors to reopen the Vietnam War wounds and was still famous in Vietnam, and was one of the Western journalists invited back to Vietnam by the General Secretary Nguyễn Van Linh to help open the country up to the Western investment.

After nine years of painstaking research and interviews Sheehan’s book followed the path of Lt. Colonel JP Vann (arguably the most written about US Advisor in the Vietnam War) along with his own ‘highway to the war’. The book highlights Vann’s time commanding Advisory Team 4 in the Mekong Delta (where he advised the ARVN 7th Infantry Division) during 1962/3 and details how the lessons of Ap Bac were lost in the fixation with the enemy body count and the trap of American overconfidence.

US commander General Harkins described the Battle of Ap Bac as a major victory for the South Vietnamese Government, with the ARVN reported as having killed 118 VC for few casualties. It was the narrative of the time and one that few wanted to ‘lift the lid’ on the conventional wisdom that US Advisors would help the ARVN win this war in three years (by 1965).

What wasn’t highlighted was how, for the first time, the VC dug in and stood and fought, in large numbers (around 350) and survived the US dive bombers, the napalm, the daisy cutter bombs, the helicopter gunships and their mini-guns, and the APC cavalry charges.

Even more of a shock was how the VC now had developed new tactics for shooting down helicopters, using captured machine guns, before withdrawing under the cover of darkness. Not known at the time was the role of Phan Xuan An, the Times reporter, who was the Communist’s top spy in Saigon, and who was privy to the US and ARVN training and tactical information during the introduction of the helicopters in 1962, which had been so effective rounding up the small unit VC attackers and had them on the run. (Only until Larry Berman’s Perfect Spy was An’s central role in advising the VC to aim out in front of the helicopters as it was on final approach; the slowest part of its descent.

How the Battle Unfolded

The Battle took place on 2 January 1963 in the Mekong Delta (IIII Corp) in the paddies north of the hamlet of Ap Bac and near the village of Tan Thoi, north-west of My Tho city. At the time the Mekong was the hotbed of fighting – not I Corp up north.

By the end of 1962 Vann’s province had racked up the highest body count of any of the 44 provinces and was pushing for the ARVN to fully General Cao to fully exploit the revolutionary airmobile warfare. He wanted the ARVN to use the H-21 Shawnee troop carrier to land blocking forces to annihilate retreating VC, and round them up with the UH-1B Iroquois gunships, later to be known as Hueys.

The VC and local militia spent more than two days preparing the Ap Bac killing ground and digging in at Ap Bac village. Crucially, they cut down bamboo and branches and laid a false rooftop over their position; perched as they were on a 2 metre high knoll of land that had been reclaimed from the paddies.

Two captured Browning machine guns were positioned at either end of the two-metre high irrigation levee encircled the village. Most of the villagers had left when the VC arrived two days before the battle. The half dozen or so who remained kept their distance.

After allowing the American chopper pilots to sleep off their hangover on New Year’s Day, the battle was commenced mid-morning on 2 January 2018. An had already fed the VC information to expect the attack that day and the VC lay in wait, watching the tree line to the south.

At approximately 10.30 am the VC saw movement 400 metres to the south, where around 100 ARVN nguy puppet soldiers walked out from the edge of the tree line in an unceasing line of soldiers walked out along the main paddy wall into the morning sunshine – marching straight towards the VC. The ARVN soldiers expected to walk up and ‘scare the horses’ with overwhelming firepower and make the VC turn and run to the slaughtered in the open by artillery and gunships.

Like had happened in previous battles in late 1962.

Except this time the US piloted spotter plane (with Vann in the rear seat) couldn’t make out the VC strength in their camouflaged positions, leaving the ARVN soldiers and US advisors on the ground in the dark. Intelligence gleaned from signals intelligence radio intercepts had reported only a light ‘hit and run’ force.

Displaying a high degree of discipline, the VC let the ARVN soldiers close to within 50 metres and then opened up with automatic and small arms fire. Within the opening minute of the fire-fight the Southern forces suffered 30 percent casualties and were refusing to return effective fire; the remainder cowering behind the low paddy walls, as their wounded bled out in the open fields. Anyone who tried to rescue them was gunned down by the VC. A stalemate ensued until the whocker, whocker, whocker and thump, thump, thump of approaching helicopters commanded the battlefield – the helicopter soldiers were coming. Reinforcements were coming. A handful of VC upped and fled, only to be shot in the back by their officers.

The machines flew high in the sky and approached from the north-west. The gaggle of helicopters began to circle the Ap Bac rice fields – eight ‘flying banana’ troop carriers with over 100 men and four ‘tadpole’ gunships. The faster Hueys abruptly peeled off, split up and disappeared behind the village to the north. The lead troop carrier commenced its final approach and aimed for a landing area 200 metres west of the VC. As advised by their Saigon spy, the VC held their fire until the lead pilot tipped the twin rotor helicopter’s nose up to bleed speed and slowed its descent into the rice paddy.

Both Browning’s interlocked their guns and delivered a broadside against the thinly built chopper, causing bits of the H-21’s thin metal cabin to spray up into the air. The troop carrier’s left door-gunner returned fire with his flex-mounted, M-60 machine gun until he was hit and knocked back into the cabin. The chopper listed badly to the left before it reverted to horizontal and plunged the last 20 feet into the quagmire. ARVN troops immediately poured out of the rear cabin doorway. The first three troopers were cut down by withering fire. The remainder of the squad trampled over them in slow motion as they sought to find cover.

The helicopter gunships made strafing runs up and down the VC tree line with their M134 Gatling guns but to little effect. The VC held firm. ARVN artillery then opened up but was misdirected and landed amongst the troop carrier helicopters as they came into land next to the first upturned ship. All made the same mistake landing within the 300 metre effective range of the Browning’s and small arms, with five put out of action.

The VC displayed fire control and conserved ammo for the rest of the day. They survived the enemy artillery, dive bombers and gunships; and even a late in the day cavalry charge by a dozen M-113 APCs with .50 cal machines guns and one flame thrower.

An Ap Bac Emulation Drive was launched in the North, with images of the victory on postcards and billboards around Hanoi and providing a signpost to the North’s victory. In the South, the battle was recast and spun by General Harkins as a great victory, with some reports claiming the ARVN had killed 118 VC.

In reality, the 350 VC had inflicted over four times the causalities on the Saigon forces, killing 80 ARVN soldiers and three Americans for the loss of 18 VC. They had fought all day against a force four times its size and withstood 600 artillery shells, over 8,400 rounds of machine gun fire and 100 rockets on their tree line from helicopter strafing runs.

Incensed by the South’s bungling of the battle, and hurt by the loss of his comrades, Vann delivered a broadside against the Saigon General’s interference and the ARVN junior officers’ reticence to engage the enemy, as part of his after-action interview with New York Times reporter Neil Sheehan. Critical of the South, Vann respected the ‘raggedy-ass little bastards’ and said of the Communists, “They [the VC] were good men. They gave a good account of themselves today.”

Vann would go on to become one of the best known US Advisors of the war. The North’s Ap Bac Emulation Drive would stoke the fire of Comrade Number 3’s Le Duan’s ‘South First’ policy and the ARVN would go on to fight well in the final years of the war during 1973-75. But it took Neil Sheehan nine years of interviews and writing to produce A Bright Shining Lie (1988) to lift the lid on the Battle of Ap Bac and re-evaluate how the US and the Free World Forces, including Australian and New Zealand, ignored the warnings signs and were drawn deeper into the Vietnam War.

Roger Rooney is a history writer who lives in Canberra, Australia. His first novel, True North, HALO drops the reader into the battle of Ap Bac. Told from both sides, True North has been highly acclaimed by SPR “a fearless blend of history, romance, philosophy and, most importantly, brutal truth…this book attacks on all fronts,” and was described by award-winning historian Robert Macklin as “Utterly gripping.” Paperback available on Amazon for $19.95 US.

Photo – The author visited the Ap Bac paddy field in 2018 and was met by stifling heat and a serene paddy field, complete with orange trees and war tourism billboards. These emulation drive type billboards depicted APCs on fire (which didn’t happen) and a bogus bomb crater, complete with fake bomb suspended over a plastic lined dam. Another example of how the narrative is changed over time. (Photos supplied)